| ALL |

|

FASCIST ARCHITECTURE

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

Fascist architecture denotes the spectrum of architectural projects that were built, theorized, ritualized, and polemically debated by Fascist political regimes of World War II. Extreme right-wing totalitarian dictatorships were forcibly installed in Italy (1922–43), Germany (1933–45), and Spain (1939–75). The Italian Fascist Party under the leadership of Benito Mussolini, the National Socialism Party headed by Adolf Hitler, and the Falange Espanola Party led by General Francisco Franco formed coercive governments whose absolute power abolished all forms of political opposition. Public utilities, commercial exchanges, processes of industrialization, as well as the production of art and architecture were controlled and regulated by the state; and it was in Italy and Germany that architecture played a seminal role in the advancement of Fascist ideologies.

The very term Fascism (or fascismo in Italian) was derived from the Latin word fasces, denoting an ornamental object of political and military authority carried by ancient Roman lictors during public ceremonies. As early as 1919, Mussolini adopted the fasces as the emblem of the Fascist Party, intent as he was on associating the glories of ancient Rome with the future triumphs of his Fascist state.

Throughout the Fascist era in Italy architecture was used as a rhetorical device; it became the preferred vehicle for launching Fascist propaganda. It most forcefully portrayed, in the solidity of its materials and the vastness of its measures, the sublimity of imperial power. Buildings, piazzas, and ruins were privileged backdrops for public demonstrations, ritual reenactments, and oratorical theatrics; spectacles aimed at cultivating a Fascist body politic. Italian architects Giuseppe Terragni, Marcello Piacentini, Adalberto Libera, Giovanni Michelucci, and Giuseppe Pagano participated in the design of new building types, the inauguration of new colonies, the restoration of ancient monuments, the staging of political rallies, the mounting of exhibits, and the publication of polemical journals; activities that contributed to the construction of the new Roman Empire.

From the outset, Mussolini launched a massive building campaign. The modernization and nationalization of transportation and communication networks necessitated the design and construction of building types new to Italian soil. Modern and efficient railway stations and post offices were built throughout Italy. Florence’s Santa Maria Novella train station (1932–34), designed by Gruppo Toscano (a six-member group of Florentine rationalists), and Rome’s Palace of Postal and Telegraphic Services, designed by BBPR (Banfi, Belgiojoso, Peresutti, and Rogers), were only two of the many building projects sponsored by the state. It was the invention of the Casa del Fascio (House of the Fascist Party), however, that most captivated the Italian imagination. Used primarily as the local headquarters of the Fascist Party, versions of this new building type were erected throughout the Italian peninsula. Typically sited in the center of town, the structure rivaled the church’s dominance and evidenced the ceaseless presence of Il Duce. The most celebrated Casa del Fascio was built in Como (1932–36) and designed by Giuseppe Terragni. Its monumental austerity, abstract formalism, and frontal transparency made it the building most representative of both Italian Fascism and modernism.

Mussolini also commissioned the construction of entirely new towns in the southern regions of the Roman Campania, in Sardinia, in the Greek Dodecanese, and in the colonies of northern Africa. The towns of Littoria, Carbonia, and Guidonia were built on reclaimed swampland, whereas the occupied cities of Tripoli, Bengazi, Kos, and Rhodes were resettled with Italian farmers. Predappio (1925), Mussolini’s hometown, was the first to be built with wide avenues, monumental civic buildings, and a vast civic piazza. Littoria (1932), named after the lictor who had carried the ceremonial fasces during antiquity, was built with the knowledge of ancient Roman foundation rites.

Antiquity was equally of issue in the Fascist policy of “isolamento”: the valorization and preservation of rhetorically significant buildings. In an attempt to make visible select architectural masterpieces from imperial Rome, monuments from the first century BC were liberated from thousands of years of historical and material growth. With the demolition of entire city blocks, the Mausoleum of Caesar Augustus (63–14 BC) became one such site. Symbolic of the burial ground of Rome’s founding emperor, the unearthing of its sublime circular structure was completed in 1937, the 2,000th anniversary of his birth. With a similar intent, Mussolini effected vast transformations to the via delI’Impero (present-day via dei Fori Imperial!) by physically connecting the ruins of the Colosseum with the administrative center of Fascist Rome—Piazza Venezia. In an effort to valorize the Roman Forum and the Forum of Augustus, the via dell’ Impero was designed as a monumental avenue for ceremonial and military parades.

Alongside the building of large-scale architectural interventions, architects also participated in the design and construction of exhibits. Throughout the Fascist era, the mounting of statesponsored public exhibitions was a significant vehicle for the promotion of both architectural ideas and Fascist polemics. In March 1931, the International Movement for Rational Architecture (MIAR) opened its second exhibition with a critique of contemporary Italian architecture. The likes of Pietro Maria Bardi, Edoardo Persico, and Alberto Sartoris called for the radical alliance of Fascist doctrine with modern architecture, for only in this way could a true renewal of the country take place. In 1932, to mark the tenth anniversary of the Fascist takeover of power, the Mostra delta Rivoluzione Fascista (Exhibit of the Fascist Revolution) featured the work of architects Libera, Mario Renzi, and Terragni, its pavilions manifesting the allegiance of modernism to Fascist doctrine. However, it was the Universal Exposition of 1942 (EUR’42) that placed the Italian Fascist state on display through its vast complex of monumental pavilions, designed under the leadership of Piacentini. Although the events of the war halted its completion, the polemics surrounding the construction of EUR’42 forcefully pitted the modern rationalists against the more conservative neoclassicists.

Journals, periodicals, and newspapers were also significant venues for the dissemination of both architectural theory and Fascist propaganda. The printed word and image had become highly effective means of communication, and as a former journalist Mussolini was well aware of this truth. Marcello Piacentini served as editor for Architettura, and Quadrante was edited by Pietro Maria Bardi. Casabella was founded in 1928, and in 1933 Giuseppe Pagano had become its editor. Along with Quadrante, Casabella had been a vocal supporter of the Italian rationalists, and in the final years of the Fascist regime, with increasing criticism levied against the state, the magazine was ordered to cease production. As a result, architects Pagano and Banfi were deported to German death camps.

In Germany, the totalitarian regime of National Socialism, led by the Fuhrer Adolf Hitler, also privileged architecture in the communication of its ideologically charged political agenda. In Nazi Germany architecture, of all the visual arts, was materi-ally, spatially and structurally most representative of the dictatorial power of the III Reich, a state intent on the political and military conquest of the Western world.

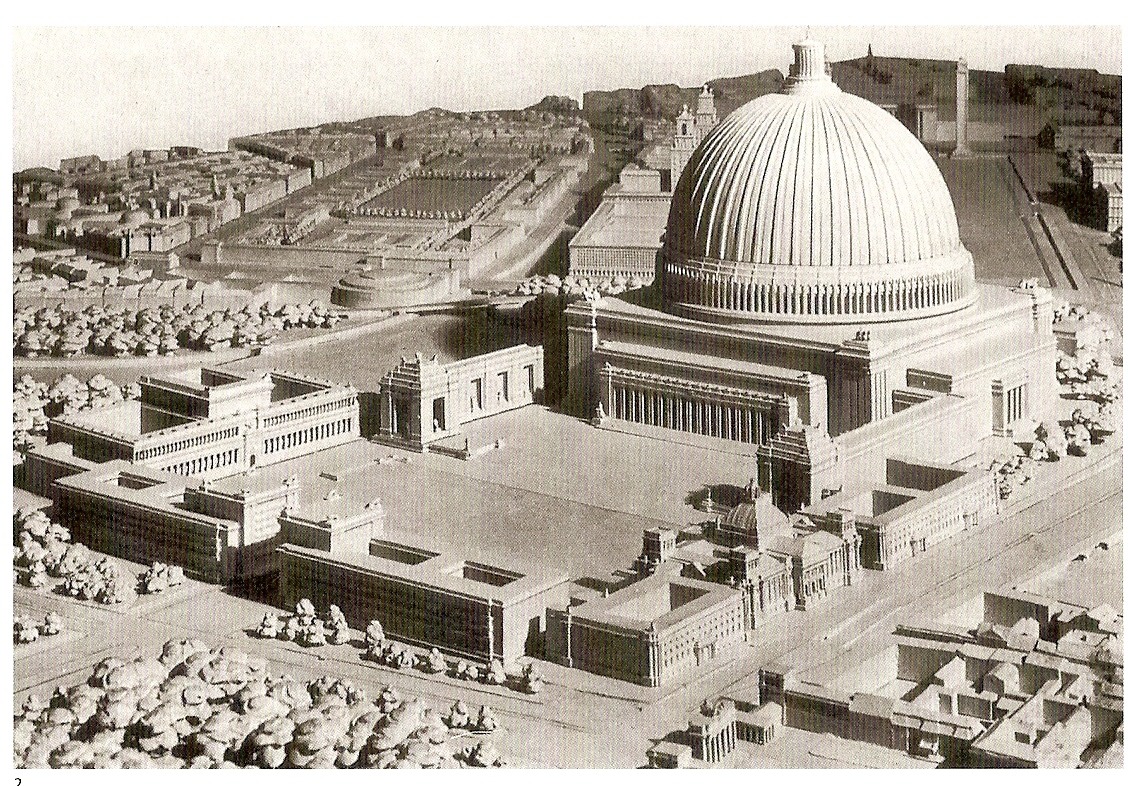

In this venture was implicated architect Albert Speer, who in 1937 was named by Hitler Inspector General of Buildings (GBI, Generalbauinspektor). The title attributed to Speer expansive decision-making powers and the mandate to make of Berlin a capital embodying the tenets of National Socialism. Guided by Hitler’s own artistic imagination, Speer embarked on the conceptualization and design of the largest building project initiated by any totalitarian regime, the construction of a new urban plan for the city of Berlin. The enormous project envisioned the rezoning of a vast territory of the city through which the destruction of tens of thousands of homes would have been assured.

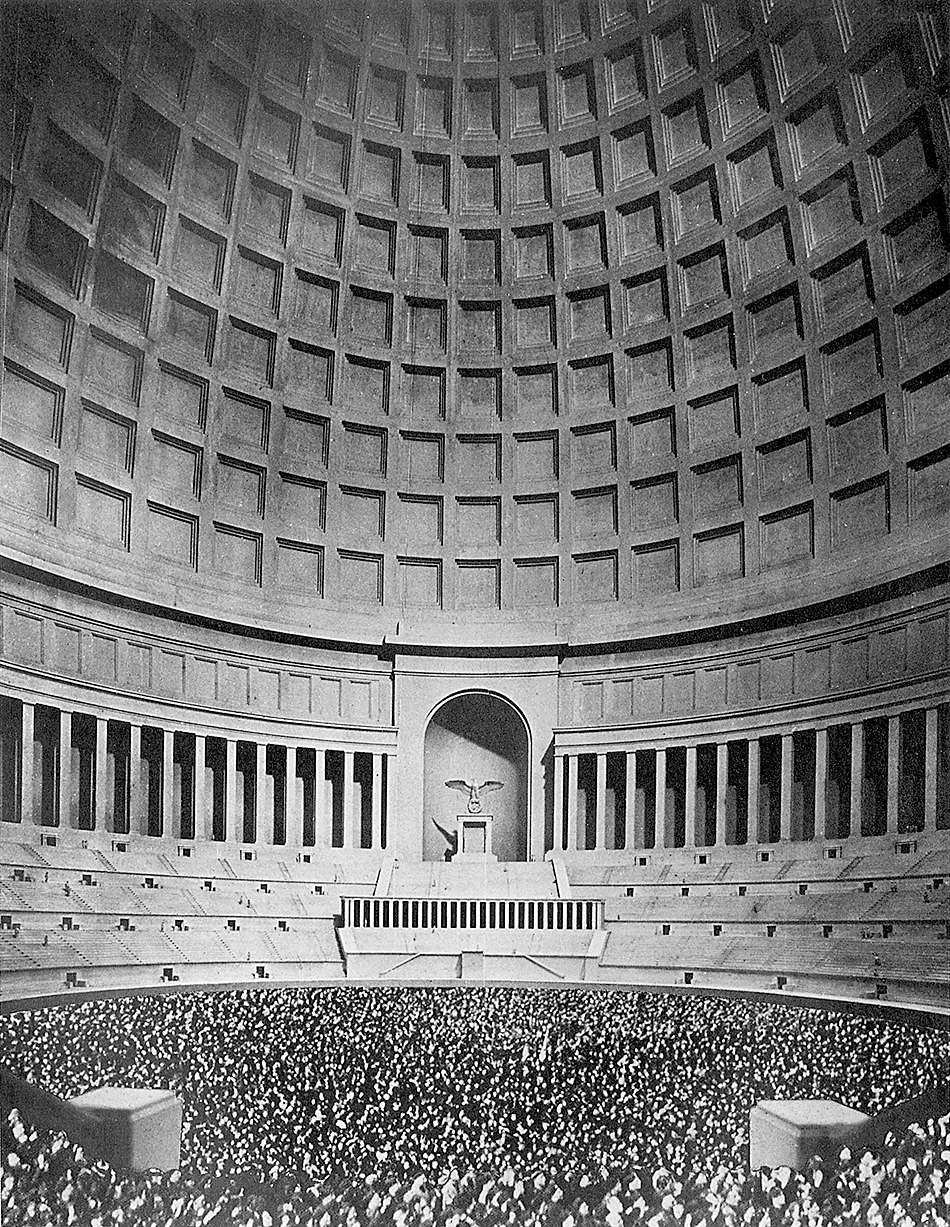

If actualized, the plan would have forcibly introduced a monumental north/south axis five kilometers long, originating at the southern limit of the Tempelhof and Schoeneberg districts and terminating at the city’s northern limit, the Spree. Lined with granite-clad buildings, the axis would have housed the most politically significant buildings representative of the III Reich’s major ministries and centers of power. At its northern end, the axis was designed to incorporate the colossal Pantheonlike shaped building called the Great Hall, conceived to gather nearly 200,000 spectators in mass celebrations of National Socialism. But steps from the Brandenburg gate, the Great Square immediately to the south of the Great Hall would have been surrounded by Hitler’s Palace, the High Command of the Armed Forces, the New Chancellery, and the Old Reichstag. And although the New Chancellery was inaugurated in January 1937, Speer would have designed all of the square’s new buildings.

Completed as planned, the monumental scale of the north/ south axis would have engendered a sense of domination never before achieved by human artifice. And notwithstanding Hitler’s defeat that ensured the demise of the Berlin project, Speer incorporated many of its architectural strategies in earlier projects for another German city, Nuremberg. In 1936, Speer completed the redesign and extension of its Zeppelin Field, a parade ground for the mass gathering of 100,000 citizens. In the austerity of its neoclassical colonnade and in the massive extension of its 1,000-foot reviewing stand was achieved a rhetorical and ideological backdrop for the orchestration of party rallies and for gatherings of the Hitler Youth movement. Thus, in both Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, architecture was used as a highly articulated tool of political propaganda. That architects were directly involved in the production and communication of such beliefs should not be overlooked but rather the source of continued study.

FRANCA TRUBIANO

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.1 (A-F). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2004. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1931-1934, Florence’s Santa Maria Novella train station, Florence, ITALY, Gruppo Toscano |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1932-1936, Casa del Fascio, Como, ITALY , Giuseppe Terragni |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1934, Post Office, Sabaudia, ITALY, Angiolo Mazzoni |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1936, Zeppelin Field, Nuremberg, GERMANY, Albert Speer |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

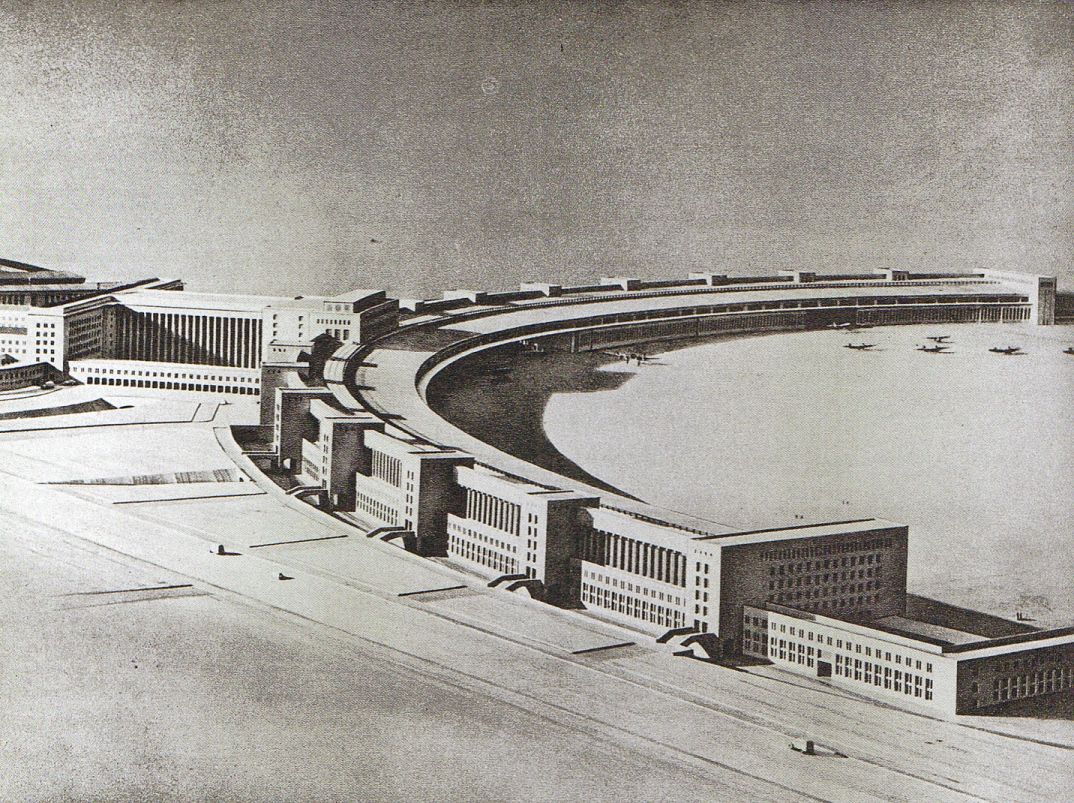

1936-1939, Tempelhof Airport model, Berlin-Tempelhof, Germany, Ernst Sagebiel |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1936-1939, Tempelhof Airport, Berlin-Tempelhof, Germany, Ernst Sagebiel |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1937, Unterdenlindenstrasse, decorated for Mussolini's visit, Berlin, Germany |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1937-1942, Palace

of Italian Civilization,

Rome, Italy, Giovanni Guerrini,

Ernesto Bruno la Padula,

and Mario Romano |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

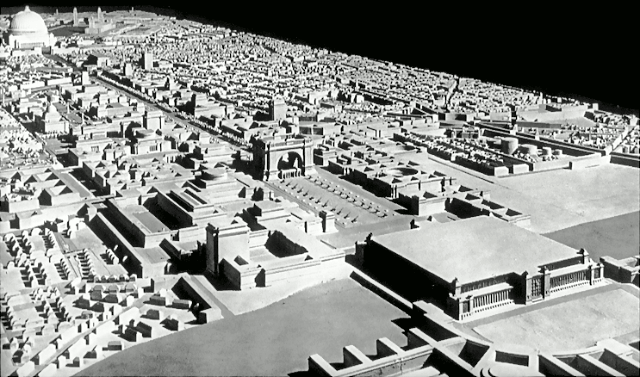

1937-1943, Grand Avenue, Dome, and Are de Triomphe, model for Berlin, Germany, Albert Speer |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1937-1943, Great Hall, plan for Berlin, Germany, Albert Speer |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1937-1943, Great Hall, plan for Berlin, Germany, Albert Speer |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1938, Casa del Fascio, Guidonia, Italy, Giorgio Calza |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

Gruppo Toscano

TERRAGNI, GIUSEPPE

Albert Speer |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1931-1934, Florence’s Santa Maria Novella train station, Florence, ITALY, Gruppo Toscano

1932-1936, Casa del Fascio, Como, ITALY , Giuseppe Terragni

1936, Zeppelin Field, Nuremberg, GERMANY, Albert Speer |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

FURTHER READING

Bruxelles: Aux Archives d’architecture Moderne, 1985

Ades, Dawn, et al. (compilers), Art and Power: Europe under the Dictators, 1930–1945 (exhib. cat.), London: Hayward Gallery, 1995

Andreotti, Libero, “The Aesthetics of War: The Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution,” Journal of Architectural Education 45 (February 1992)

Doordan, Dennis P., Building Modern Italy: Italian Architecture, 1914–1936 , New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1988

Ghirardo, Diane Yvonne, Building New Communities: New Deal America and Fascist Italy, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1989

Ghirardo, Diane Yvonne, “Architecture and Culture in Fascist Italy,” Journal of Architectural Education 45 (February 1992)

Jaskot, Paul, The Architecture of Oppression, London: Routledge, 2000

Kostof, Spiro, The Third Rome, 1870–1950: Traffic and Glory, Berkeley, California: University Art Museum, 1973

Miller Lane, Barbara, Architecture and Politics in Germany 1918–1945, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1968.

Millon, Henry, “Some New Towns in Italy in the 1930s” in Art and Architecture in the Service of Politics, edited by Millon and Linda Nochlin, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1978

Schumacher, Thomas L., Il Danteum di Terragni, 1938, Rome: Officina Edizioni, 1980; enlarged and revised edition, as The Danteum: A Study in the Architecture of Literature, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton Architectural Press, 1985 |

| |

|

|